News

.jpg%3F1752954353)

Germany women win thriller against France to advance to semi-finals

Germany’s women’s national team have reached the semi-finals of the UEFA Women’s EURO, after a hard-fought win against France (1-1 a.e.t., 6-5 on pens.).

"Future Leaders": participants from 25 countries attend leadership programme in Lörrach

The UEFA Women's European Championship tournament was the fitting stage for young role models to meet – both on and off the pitch. The participants of the "Future Leaders in Football" (FLF) leadership programme came to Basel to watch Germany play.

EURO 2024 Climate Fund: €7.9 million invested in grassroots sustainability projects

The UEFA EURO 2024 Climate Fund has officially concluded, resulting in a total of €7.925 million invested in sustainable initiatives across Germany’s grassroots football landscape.

Germany women end EURO group stage with 4-1 defeat to Sweden

Germany’s women’s national team fell to a 4-1 defeat against Sweden at the Stadion Letzigrund in Zurich, in what was their third and final group stage at the UEFA Women’s EURO.

Germany through to quarter-finals after 2-1 win against Denmark

Germany’s women’s national team won 2-1 against Denmark in their second group stage match at the UEFA Women’s EURO and have booked their place in the quarter-finals.

Gwinn suffers MCL injury in left knee

Giulia Gwinn will miss the rest of EURO 2025. The Germany women’s national team captain suffered an MCL injury in her left knee during her team’s opening game of the tournament against Poland on Friday. She is expected to be out for several weeks.

.jpg%3F1751661424)

Germany women beat Poland in EUROs opener

Germany’s women’s national team won their opening game of UEFA Women’s Euro 2025. Head coach Christian Wück’s side beat Poland 2-0 in their first group match. Jule Brand and Lea Schüller found the net in front of 15,972 spectators in St. Gallen.

“Gender Equality”: Sixth “Future Leaders in Football” workshop underway

The DFB is hosting its “Future Leaders in Football” development programme for the sixth time. The six-day workshop is taking place in Lörrach, right on the border with Switzerland, the host of the ongoing EUROs.

U21s beaten by England in EUROs final

Germany U21 were defeated in the final of the EUROs in Slovakia. In front of 19,153 spectators in Bratislava, head coach Antonio Di Salvo’s side lost 3-2 in extra time to England, who lifted the trophy for a fourth time.

Di Salvo: “It’s an evenly matched game”

On Saturday (21:00 CEST), Germany U21 face England in Slovakia as they look to lift the U21 EUROs trophy for the fourth time. Head coach Antonio Di Salvo and top goalscorer Nick Woltemade spoke on Friday ahead of the final.

U21s reach EUROs final with 3-0 win over France

The Germany U21 national team has reached the final of the European Championship in Slovakia after head coach Antonio Di Salvo’s team beat France 3-0 in the semi-final. They face England for the crown on Saturday.

Times and dates of 2025/26 DFB-Pokal first-round ties announced

The DFB has announced the times and dates for the first round of the 2025/2026 DFB-Pokal. 30 matches have been scheduled between 15th and 18th August, with two further ties to be played on 26th and 27th August.

Germany through to U21 EURO semi-finals after 3-2 win against Italy

Germany have progressed to the semi-finals of the U21 EUROs in Slovakia following a 3-2 win (a.e.t.) against Italy.

2-1 win over England confirms quarter-final against Italy for U21s

The Germany U21 national side also won their third group game at the European Championship in Slovakia. Antonio Di Salvo’s team beat holders England 2-1 in front of 5,624 fans in Nitra on Wednesday night.

DFB extends Nia Künzer’s contract as sporting director until 2029

The German Football Association (DFB) and sporting director Nia Künzer have agreed an early extension of her contract until 2029.

.jpg%3F1750017751)

U21s secure EUROs quarter-final spot with 4-2 win over Czechia

The Germany U21 national team won the second match of their European Championship campaign in Slovakia to book a place in the quarter-finals of the competition. Head coach Antonio Di Salvo’s side emerged 4-2 victors over Czechia in Dunajska Streda.

FC Bayern visit SV Wehen Wiesbaden, Braunschweig host Stuttgart

SV Wehen Wiesbaden will host Bundesliga champions and record cup winners FC Bayern München in the first round of the upcoming DFB-Pokal campaign. Last season’s victors VfB Stuttgart travel to face Eintracht Braunschweig, as decided by Sunday's draw.

DFB confirms host cities for Women’s EURO 2029 bid

The Presidential Board of the German Football Association (DFB) has today confirmed the eight host cities that will be included in Germany’s official bid dossier for UEFA Women’s EURO 2029.

Woltemade nets hat-trick in opening U21 EUROs match against Slovenia

The Germany U21s kicked off their U21 European Championship campaign with a 3-0 win against Slovenia.

Wück: “If we play to our best, anything is possible”

Christian Wück announced his squad for the UEFA Women’s EUROs in Switzerland (2nd to 27th July) on Thursday afternoon The Germany coach and sporting director Nia Künzer discussed the squad and their chances of winning the tournament.

Wück announces squad for UEFA Women’s EUROs in Switzerland

National team head coach Christian Wück announced his squad for the UEFA Women’s EUROs in Switzerland on Thursday. The Germany women’s national team cohort comprises 20 outfield players and three goalkeepers and is led by captain Giulia Gwinn.

Sara Doorsoun retires from international duty

Sara Doorsoun has retired from duty with the Germany Women’s national team. The Eintracht Frankfurt defender, who will continue her career at club level, racked up 59 international caps, winning an Olympic Bronze medal at Paris 2024 along the way.

Kimmich: "With six minutes gone, we should have been 3-0 up"

Despite a plethora of first-half chances, the Germany national team suffered a 2-0 defeat at the hands of France, meaning they finish ultimately the Nations League in fourth place. DFB.de has rounded up the post-match reaction.

Germany lose third place play-off against France

Germany ended the latest edition of the UEFA Nations League in fourth place. Julian Nagelsmann’s team were beaten 2-0 by France in Stuttgart in Sunday’s third place play-off.

Joshua Kimmich: “We need to learn from this defeat”

Germany's Nations League campaign ended in frustration after a 2-1 defeat to Portugal in the semi-finals. Despite taking the lead, the DFB-Team couldn't hold on – and the reaction from players and staff was brutally honest.

Di Salvo selects final EUROs squad

Di Salvo and his coaching staff had up until 23:59 CEST on 4th June to submit their final 23-strong squad to UEFA for the European U21 Championship, cut down from the 26 players called up preliminarily.

Germany beaten in Nations League semi-final by Portugal

Germany missed their opportunity of playing a home final in the UEFA Nations League after losing the first semi-final 2-1 to Portugal in Munich.

.jpg%3F1748979856)

Comfortable win for Germany Women in final game before European Championship

Germany’s women’s national team won their final UEFA Nations League group game 6-0 away against neighbours Austria.

.jpg%3F1748973731)

Nagelsmann: "Our confidence is only growing"

The Germany national team’s UEFA Nations League semi-final clash with Portugal on Wednesday is fast approaching. Julian Nagelsmann and Leon Goretzka spoke ahead of the match about the significance of the tournament and the strengths of the opponent.

Kimmich ahead of his 100th cap: “It means a lot to me”

Joshua Kimmich is set to win his 100th cap for Germany in Wednesday’s UEFA Nations League semi-final (21:00 CEST) against Portugal at his home ground in Munich. Ahead of this week’s fixture, the Germany captain talked about the milestone.

Germany Women cruise past the Netherlands to reach Nations League Final Four

Germany’s women’s national team have secured their place in the UEFA Women’s Nations League Final Four with a convincing 4-0 win over the Netherlands in their penultimate group match.

Nagelsmann: "We want to keep building our identity"

Germany take on Portugal in Munich on Wednesday night (21:00 CEST) for a place in the UEFA Nations League final. Head coach Julian Nagelsmann and sporting director Rudi Völler spoke about the upcoming semi-final and the team’s preparations.

Burkardt added to Final Four squad

Germany head coach Julian Nagelsmann has added 1. FSV Mainz 05 forward Jonathan Burkardt to his squad for the upcoming Final Four of the UEFA Nations League.

Stuttgart clinch fourth DFB-Pokal title with 4-2 win over Bielefeld

After previously taking the title in 1954, 1958 and 1997, VfB Stuttgart are German cup winners for the fourth time. The 82nd DFB-Pokal final saw them defeat third-division champions Arminia Bielefeld 4-2 at the Olympiastadion in Berlin.

Benjamin Hübner to become new assistant coach of German national team

Benjamin Hübner will become the new assistant coach of the German national team. The 35-year-old will replace Sandro Wagner in Julian Nagelsmann’s coaching team after Wagner leaves the role at the start of June.

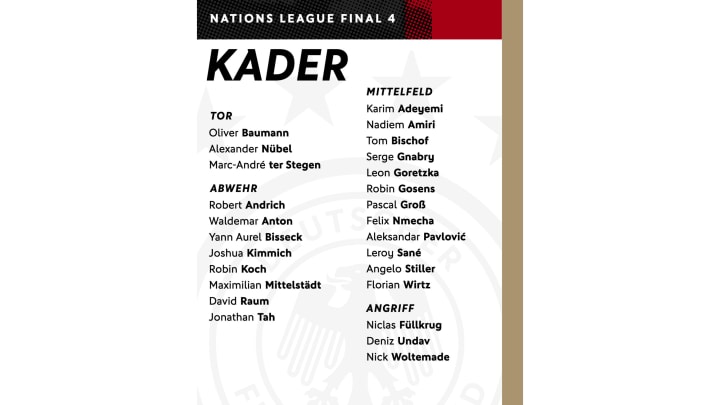

Bischof and Woltemade called up to Nagelsmann’s 26-player Nations League squad

Germany national team head coach Julian Nagelsmann announced his 26-player squad for the UEFA Nations League Final Four on Thursday. Captain Joshua Kimmich of German champions FC Bayern München is set to receive his 100th international cap.

Di Salvo selects preliminary squad for U21 EUROs

Germany head coach Antonio Di Salvo has announced his preliminary squad for the European U21 Championship, which will take place between 11th and 28th June in Slovakia.

Five players return to Wück’s squad

National team head coach Christian Wück has announced the Germany women’s squad for the upcoming UEFA Women’s Nations League games against the Netherlands (30th May in Bremen) and Austria (3rd June in Vienna).

FC Bayern secure second Women’s DFB-Pokal title

FC Bayern München have added the DFB-Pokal to their haul of trophies this season after also clinching the 2024/2025 German league title and in doing so have secured their first domestic double in club history.

Sandro Wagner to leave DFB-Team in summer

Following discussions with Germany national team head coach Julian Nagelsmann, current assistant coach Sandro Wagner has decided to leave the DFB following the conclusion of the UEFA Nations League Final Four.

Germany women rally to beat Scotland 6-1

After trailing 1-0 at half-time, the Germany women rallied after the break to beat Scotland 6-1 in the UEFA Women’s Nations League.

Germany Women win 4-0 in Scotland

Germany have extended their unbeaten streak in the UEFA Women’s Nations League thanks to a 4-0 win over Scotland in Dundee. Senß, Zicai and Schüller all scored for Christian Wück’s side, while Scotland’s Howard also turned into her own net.

World Cup winner Hummels to retire at the end of the season

World Cup winner Mats Hummels will retire in the summer. The 36-year-old, who currently plays for Italian club AS Roma, announced on Friday that he is set to end a successful career at the conclusion of the season.

VfB Stuttgart through to DFB-Pokal final after 3-1 win against RB Leipzig

VfB Stuttgart have reached the final of the DFB-Pokal for the seventh time in their history after a 3-1 win against RB Leipzig in the semi-finals.

Bielefeld knock out defending champions Leverkusen to advance to DFB-Pokal final

Arminia Bielefeld shocked defending champions Bayer 04 Leverkusen to reach the DFB-Pokal final for the first time in the club’s history after a 2-1 win.

Almuth Schult announces decision to end career

Almuth Schmidt announced today that she will end her career in professional football. The goalkeeper is not only retiring from the Germany national team but also at club level. The 34-year-old racked up a total of 66 Germany caps.

.jpg%3F1742934172)

Woltemade hat-trick secures 3-1 win against Spain U21s

Germany U21s ran out 3-1 winners against Spain U21s in Darmstadt, courtesy of a hat-trick from Nick Woltemade.

Head coach Wück hands Franziska Kett first call-up

National team head coach Christian Wück has announced his 23-player squad for the upcoming UEFA Women's Nations League fixtures with Scotland. 20-year-old Franziska Kett of FC Bayern München has received her first Germany call-up.

Germany to play Slovakia, Northern Ireland and Luxembourg in their World Cup qualification group

Germany now know their opponents for their World Cup qualification campaign. Julian Nagelsmann’s team will be in group A along with Slovakia, Northern Ireland and Luxembourg.

Nagelsmann: “The first half was very impressive, unbelievably good”

Germany are into the final tournament on home soil! The national team reached the semi-finals of the Nations League after a 3-3 draw with Italy in their quarter-final second leg. DFB.de has all the reaction from the match.

Germany into Nations League semi-finals after draw in Dortmund

Germany have reached the semi-finals of the UEFA Nations League for the first time. Following their first-leg victory in Milan, Germany drew 3-3 with Italy in the second leg in Dortmund, setting up a meeting with Portugal in Munich on 4th June.

Nagelsmann: "Possession will play a key role"

The Germany national team take to the pitch once again on Sunday evening as they face Italy in the second leg of their Nations League quarter-final tie. Head coach Julian Nagelsmann and goalkeeper Oliver Baumann spoke about expectations for the game.

U21s record 1-0 win in Slovakia

The Germany U21 national team ran out 1-0 winners in their friendly match away to Slovakia in Trvana. Head coach Antonio di Salvo witnessed his team produce a solid performance as they look to gain momentum ahead of the upcoming U21 EUROs.

Nagelsmann: “The team gave everything to win the game”

Head coach Julian Nagelsmann and his players were pleased with Germany’s away win in the first leg of their UEFA Nations League quarter-final with Italy. DFB.de has all the reaction from their 2-1 win in Milan.

Goretzka and Kleindienst earn Germany away win in Italy

Germany put themselves in a strong position to progress to the semi-finals of the UEFA Nations League as head coach Julian Nagelsmann’s side came from behind to win 2-1 in the first leg against Italy at the San Siro in Milan.

Rüdiger: "It's a massive game"

Head coach Julian Nagelsmann and centre-back Antonio Rüdiger spoke to the press ahead of the first leg of their UEFA Nations League quarter-final against Italy.

.jpg%3F1742374049)

Magull announces international retirement

Lina Magull has announced her retirement from international football. The 30-year-old earned 77 caps for the Germany women's national team, scoring 22 goals in the process.

Adidas release special kit to celebrate 125 years of the DFB

In collaboration with partner adidas, the DFB have released a special limited edition kit to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the association’s founding. The shirt symbolises the emotion invoked by the special moments experienced over this period.

Two debutants named in Germany U21 squad

Head coach Antonio Di Salvo has announced his squad for the team’s first games of 2025, which will also serve as preparation for this summer's U21 EUROs.

DFB announce venues for home World Cup qualifiers

The DFB GmbH & Co. KG Supervisory Board and Shareholders’ Assembly decided on the venues for the Germany national team’s home World Cup qualifying fixtures in their meeting on Friday in Frankfurt am Main.

Di Salvo to remain Germany U21 head coach

The DFB have extended the contract of Germany U21 head coach Antonio Di Salvo by a further two years until 31st July 2027. The 45-year-old will therefore remain in charge beyond this year’s European Championship tournament in Slovakia.

Bisseck receives maiden call-up for Nations League quarter-final with Italy

On Thursday, Germany national team head coach Julian Nagelsmann named his 23-man squad for the upcoming UEFA Nations League quarter-final against Italy, with one debutant and eight returning players.

Third-tier Bielefeld welcome Leverkusen and Stuttgart host Leipzig

Holders Bayer 04 Leverkusen will travel to third-tier side Arminia Bielefeld in the semi-finals of the DFB-Pokal. VfB Stuttgart meanwhile will host fellow Bundesliga club RB Leipzig.

.jpg%3F1740605842)

RB Leipzig complete semi-final line-up thanks to Šeško penalty

RB Leipzig have taken another step towards their fourth DFB-Pokal final in the past five years. The Saxons edged out Bundesliga rivals VfL Wolfsburg 1-0 in the quarter-finals on Wednesday night, completing the line-up for the final four.

.jpg%3F1740516664)

Bielefeld stun Werder to advance to cup semi-finals

Arminia Bielefeld have progressed to the semi-finals of the DFB-Pokal following a 2-1 win against SV Werder Bremen.

Germany women victorious after 4-1 triumph against Austria

Germany’s women’s national team celebrated a 4-1 win against Austria in the UEFA Nations League on Tuesday evening. It was their first home win under head coach Christian Wück, in front of 14,394 spectators in Nuremberg.

.jpg%3F1720007147)

.jpg%3F1653759824)